Middle schoolers learned climate science by designing video games, shows Boston-area research program

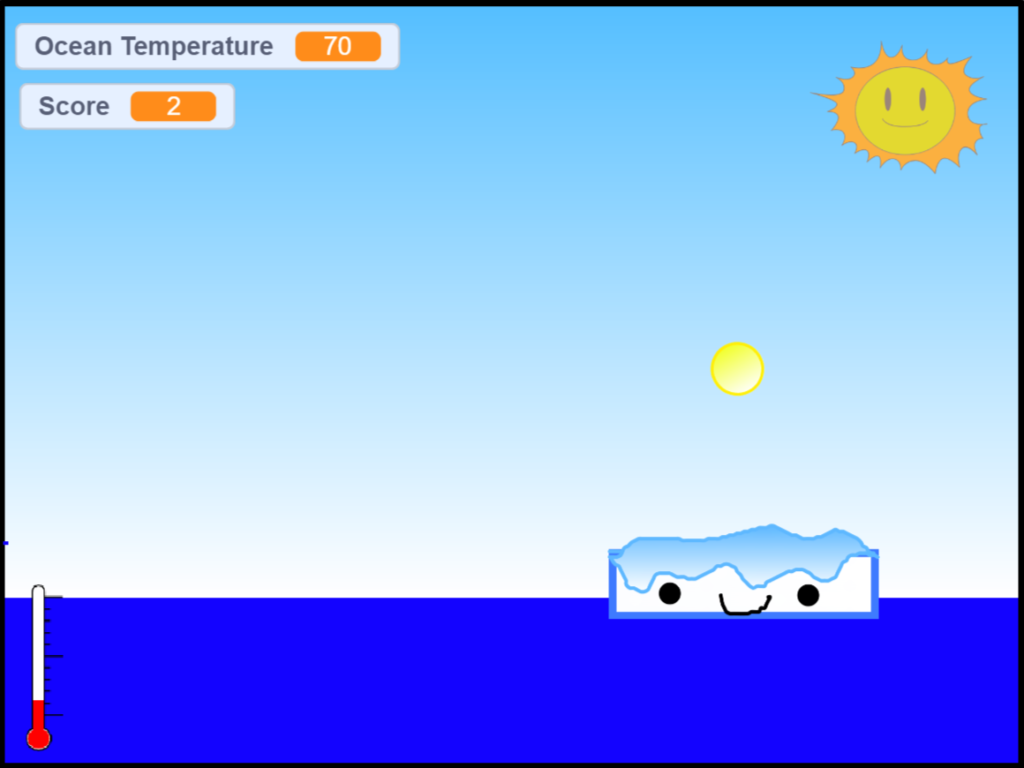

There’s a smiling sun that says, “Use the ice to reflect the sunlight and keep the ocean from absorbing heat.” So, you drag a cute little iceberg back and forth using your cursor — battling the sun, ping-pong style. But each time you miss, the light hits the water, heating it up and melting the ice. The ice dwindles and loses its smile. Then it’s gone.

This game was designed by a pair of eighth graders in an educational program called Building Systems from Scratch that explores how designing — not just playing — video games can facilitate climate change education. The program is a partnership between Northeastern game design professors Casper Harteveld and Giovanni Troiano and researchers Gillian Puttick, Eli Tucker-Raymond and Mike Cassidy at the Boston-area STEM education nonprofit, TERC.

“When you’re building a game, you need to really learn the topic, and you need to learn it very, very well,” says Harteveld. “Not only do you need to know the content and the domain you’re working with; you also need to be able to transform it. And that requires a higher level of knowledge.”

In multiple studies conducted by the Northeastern-TERC partnership to assess the efficacy of the program, they found that students demonstrated an understanding of climate systems through their games. Now, each group is building on the program to enhance game-based learning in science education.

Using game design to teach students about climate change

In 2016 and 2017, more than 900 eighth-graders from four middle schools in the greater Boston area participated in the educational program, funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF). The STEM curriculum focused on computational thinking, systems thinking and climate science. Designed by the researchers and participating teachers, the curriculum first introduced climate change topics to their students. Then, students were taught the basics of game design in the coding language, Scratch.

“The kids almost universally loved creating games and loved learning in this way,” says Gillian Puttick, one of the researchers from TERC who worked directly with the teachers and students. “When we interviewed the kids, they all said that they learned some [additional] science” to include in their game.

In one of the handful of papers on the project, published in the proceedings of the 2020 CHI PLAY Conference, the researchers found that all of the kids learned about game design, climate science and systems thinking. But only 7% percent of students performed well in all three evaluation metrics for their games — whether the game has a clear purpose, accurately reflects reality and is simply fun to play — and only an additional 24% scored positively on at least one metric.

The students who performed exceptionally impressed the researchers. For example, the pong game on the warming and melting ice feedback loop: “It’s brilliant,” says Troiano. “These kids, they have learned what systems thinking is … They understand how it maps to climate systems and they can even program a game” incorporating what they’ve learned.

For the researchers, the fact that only a small number performed exceptionally simply means the program needs to better guide and support students — and better assess them. Both the Northeastern and TERC researchers have launched their own follow-up projects to tackle these problems.

To that end, the Northeastern side launched Computational Thinking for All (CT4All). In the NSF-funded project, they’re improving existing metrics to measure learning outcomes and providing additional support and guardrails for students and teachers.

Through a project called StudyCrafter, Harteveld hopes to make game design easier and more accessible for students. The project’s site has a growing community of students, teachers, researchers, lawyers — you name it — creating games applied to real-world situations.

Inspired by a deeper educational philosophy

The learning style that the Northeastern and TERC researchers are proposing is a paradigm shift. Instead of using an “instructionist” approach to education where teachers simply lecture, they’re using a “constructionist” approach for topics that pair well with systems thinking. It emphasizes hands-on learning and building knowledge together.

“In a truly constructivist environment, you learn from your peers more than from your teacher,” says Troiano. “It’s a more distributed, democratic approach to learning.”

The constructivist philosophy is also “about kids being digital natives and much quicker to problem solve and figure things out in the digital world than adults” usually can, says Puttick. In Building Systems from Scratch, there were always “a handful of kids in the class who knew [coding] and could act as experts who could help the other kids.”

But bringing this type of education into the mainstream won’t be easy, says Puttick. Addressing systemic problems in education — like administration distrusting teachers and passing down strict, limiting guidelines — is necessary for it to thrive in the real world. And instead of giving teachers marching orders, Puttick says, school administrators need to give them room for creativity and autonomy in their teaching.

In fact, It was school administrators like this who made Building Systems from Scratch possible in the first place. “[They] created this wonderful space for us to be doing the project with those teachers because [they] grasp how engaging and exciting the opportunities are,” says Puttick.

Story from the Science Media Lab.

Last Updated on February 28, 2024