Northeastern researcher is just happy to be reunited with axolotls as campus reopens

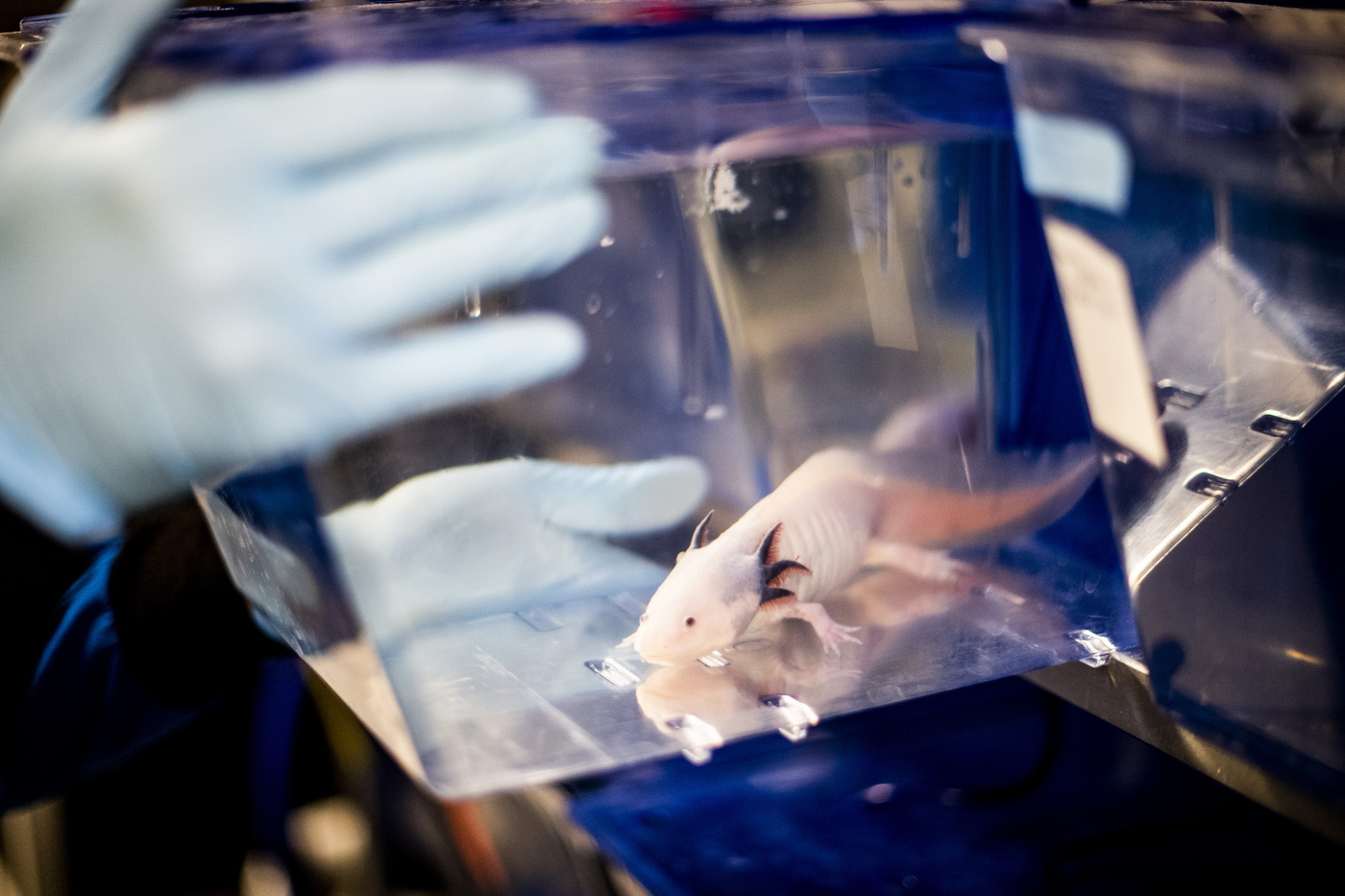

The first thing James Monaghan, an associate professor of biology at Northeastern, does on a normal day when he walks into his lab is check the animal room, where hundreds of little pink axolotl salamanders greet him as he enters. The Mexican amphibians come up to the front of their water tanks, pointing their smiling faces, adorned by fern-like gills, toward Monaghan.

But nothing is normal in 2020. And walking into his lab regularly was something Monaghan, who has been studying the salamanders because of their exceptional ability to repair injured or lost body parts, had been unable to do since March. The pandemic forced his and many other labs around the world to go on hiatus.

Monaghan’s team continued to work remotely, analyzing data. They revamped their operation to sharpen important skills, such as improving data measurement. But it was still a difficult time for someone like Monaghan, who has been studying—and spending time with—salamanders for the past 17 years.

“That was the longest I’d gone without interacting with an axolotl since my first day of graduate school,” he said recently as he sat back in his office, just a few steps down the hall from the axolotls in his lab. “The first time back in the lab was really exciting because I forgot how interactive they really can be with animal handlers.”

Monaghan’s lab consists of five graduate students and a co-op student. For them, shutting down and moving to online work in the summer meant coming together as a resilient team. Two members of the lab who lived close to Northeastern’s Boston campus stepped up and worked together to coordinate and rotate rounds of visits to care for the amphibians during the lockdown. That meant going in every single day to check on the salamanders, change their water, feed them, and monitor their health. Monaghan, who in normal circumstances would be found regularly running experiments in the lab, went in only a handful of times.

“I came in when possible, but to try to keep as much distance when I wasn’t needed, I tried to stay out of the way,” he says. “The students had such a good schedule going, and were really efficient in taking care of the animals.”

Finally, after the university allowed some researchers to begin accessing their labs in preparation for a phased reopening in the summer, Monaghan went back to his space.

“I hadn’t been that excited to go in the lab for a long time,” he says. “That was a good day.”

Still, he says, the atmosphere felt unfamiliar as he and his team prepared the lab for a new normal, ensuring that the equipment and the space were ready for reinitiating the experiments that had been paused in the spring.

“It was a little eerie, in that it felt like a lab space that reminded me of when people talk about the Mayan Empire, where it seems like everyone just got up and left one day,” Monaghan says. “That’s kind of what it felt like, because we had things that were in progress that all of a sudden were just left in limbo.”

Now, as the fall term kicks into full gear, some things are the same for the lab. The salamanders are there, and so are the scientists. But there are fewer people working together.

Tim Duerr, one of the graduate students who helped care for the salamanders during the lockdown, monitors axolotl larva in James Monaghan’s lab. Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

“It’s much quieter now,” Monaghan says. “We’re all in masks, all on our own individual benches to socially distance.”

On account of distancing guidelines the university put in place to reduce the transmission of COVID-19, the lab’s square footage limits occupancy to four people at a time. Lab members therefore spend fewer hours inside running experiments, collecting data, or discussing their research.

Everyone takes turns juggling the work of caring for the animals and conducting experiments. A morning shift is replaced by a different group that goes in the afternoon. These restrictions, Monaghan says, forced them to design and conduct research more efficiently.

“It has become less of a social event—we’ve lost a bit of that—but we’ve increased our efficiency,” he says. “I feel that experiments are planned out in more detail ahead of time and are thought out a bit more, which is good.”

Although the lab experience has changed drastically, Monaghan has no doubt that everyone on the team feels excited to be back.

“Eventually we have to get back to the experiments,” he says. “I think keeping the research enterprise active is fundamental to keep research moving forward.”

Keeping it moving forward is essential. Monaghan’s research centers on the remarkable ability of axolotl salamanders to regrow and repair their body, limbs, and organs without scarring. By exploring cellular and molecular mechanisms that scientists are just beginning to understand, his team aims to learn why the Mexican salamanders can repair tissue so effectively. In the long term, Monaghan hopes to help the scientific community figure out how to induce this ability in humans to treat diseases and injuries.

“[The axolotl] is the closest thing to us that has these really extreme regenerative powers,” Monaghan says. “There are a lot of fundamental questions that we need to address, such as how they can respond to injury, and how they know what to grow back. And what we can learn from these animals on the strategies that they use in order to turn those into future therapies.”

For media inquiries, please contact media@northeastern.edu.

Last Updated on March 23, 2021