Northeastern researchers discover new species of shipworm in Philippines

When Reuben Shipway gently drew the thin, slimy creature from its burrow in a piece of driftwood, he knew right away that he had found something special.

Shipway, a postdoctoral researcher at Northeastern’s Ocean Genome Legacy Center, was in the Philippines hunting for shipworms, a type of wood-boring clam that looks more like a worm wearing two shells as a hat than any typical bivalve.

This particular individual, found along with eight others burrowing in the same piece of wood, had uniquely-shaped pallets (small, hard structures used to plug the end of its burrow) and odd pink pinstripes on its siphons (tubes used to bring water to the gills and expel waste).

“No other species has pinstriped siphons,” Shipway says. “We knew we had something that was quite different.”

In a recent paper, the researchers announced that these shipworms, which they named Tamilokus mabinia, are not only a new species, but they are distinct enough from other shipworms to be designated an entirely new genus.

Shipway helped to discover another new genus of shipworm, announced in November of 2018, which marked the first time a new genus had been described since 1933. He is currently working with a group of researchers to describe a third.

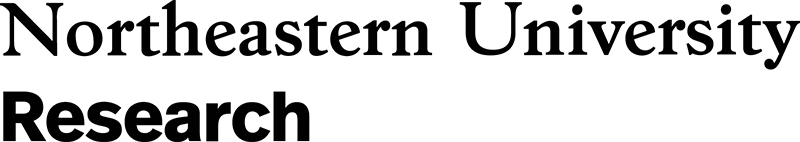

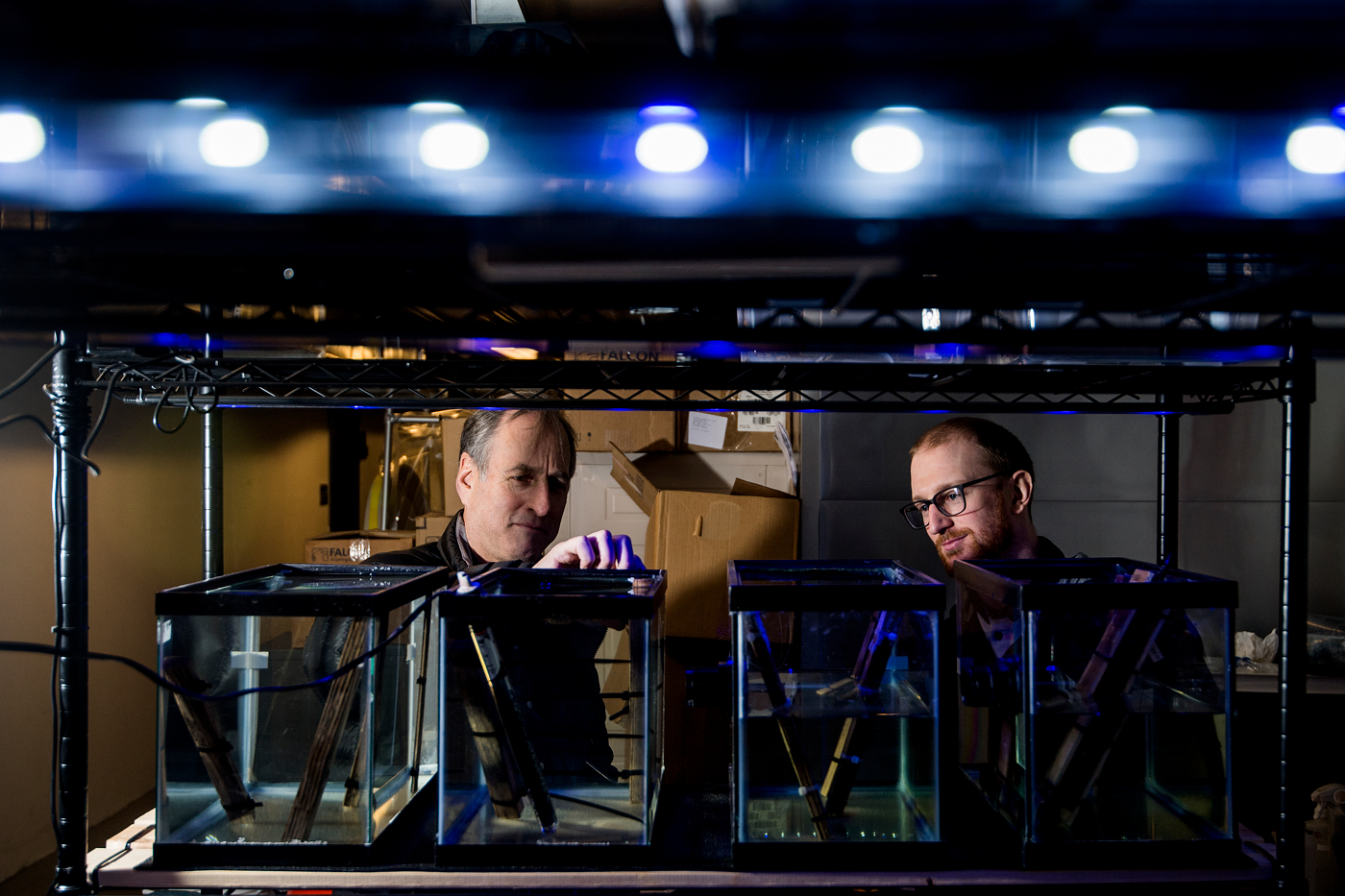

“Reuben is the shipworm whisperer,” laughs Dan Distel, who leads the research team and directs the Ocean Genome Legacy Center.

Currently there are 70 recognized species of shipworms, broken into 17 genera (including Tamilokus). They can be found in every ocean in the world, living in driftwood, mangroves, seagrass roots, and mud. They can sink a wooden vessel just by munching on it. Some species are smaller than your pinky, while the largest is more than 5 feet long.

All this diversity developed fairly quickly, Distel says. Roughly 150 million years ago, the ancestors of modern shipworms looked like ordinary clams.

“When something evolves so quickly, it’s really hard to develop a set of characteristics that can differentiate species.” Distel says. “There isn’t just one thing that makes Tamilokus different from others. It’s a whole constellation.”

In addition to the exterior differences, the researchers found that Tamilokus has an unusually large digestive tract, containing an oversized version of a rubbery, rod-shaped structure called a crystalline style. Crystalline styles are thought to aid with digestion in clams, oysters, and other bivalves.

“It basically acts like a mill,” Shipway says. “It will rotate and help break down particles by grinding them against a thickened part of the stomach.”

Photo by Matthew Modoono/Northeastern University

In most shipworms, the style is small, less than half the size of the shells that shipworms use to bore into wood. In Tamilokus, the style is twice as long as the shells, extending down into the body.

To accommodate the size of the style, Tamilokus also has an entirely new structure that the researchers are calling the “cephalic collar,” which sits just below the shells. (“It’s like a little ascot,” Distel says.) The researchers think this area may expand and contract to help move the enormous style.

The work is part of an ongoing collaboration funded by the National Institutes of Health, to study molluscs in the Philippines and the bacteria that live in them. In addition to yielding promising options for human medicine, the project has provided the opportunity for Distel, Shipway, and their colleagues to significantly advance the scientific understanding of shipworms.

“We’ve made some really stunning biodiversity discoveries on shipworms and wood borers in the last couple of years,” Shipway says. “This is a really, really exciting moment.”

For media inquiries, please contact Shannon Nargi at s.nargi@northeastern.edu or 617-373-5718.

Last Updated on January 31, 2022