Old-school social networks can help us understand “delinquent” student behavior

Northeastern’s Cassie McMillan, Assistant Professor of Sociology and Criminology and Criminal Justice, is interested in the traditional sense of the term “social network” — not Facebook friends or Instagram followers, but the groups of people we know well and interact with in person. She merges statistics and sociology to better understand how these interactions influence youth “delinquency” — a social science term that refers to behaviors like vandalism, use of explicit substances or truancy.

Her current exploration is how normative school transitions — from elementary to middle school and middle to high school — create social dynamics that affect delinquency. Existing research tends to show that these transitions result in an average decrease in these kinds of behaviors. McMillan had a hunch that shifting peer groups were a part of it.

To get to the bottom of this trend, McMillan constructed social networks for youth groups who did and did not experience these school transitions. In two studies published in 2022 and 2023, she used data from the Promoting School-Community Partnerships to Enhance Resilience (PROSPER) study. Between 6th and 12th grades, PROSPER annually surveyed 14,000 students across 28 small public school districts about their behaviors and friendships.

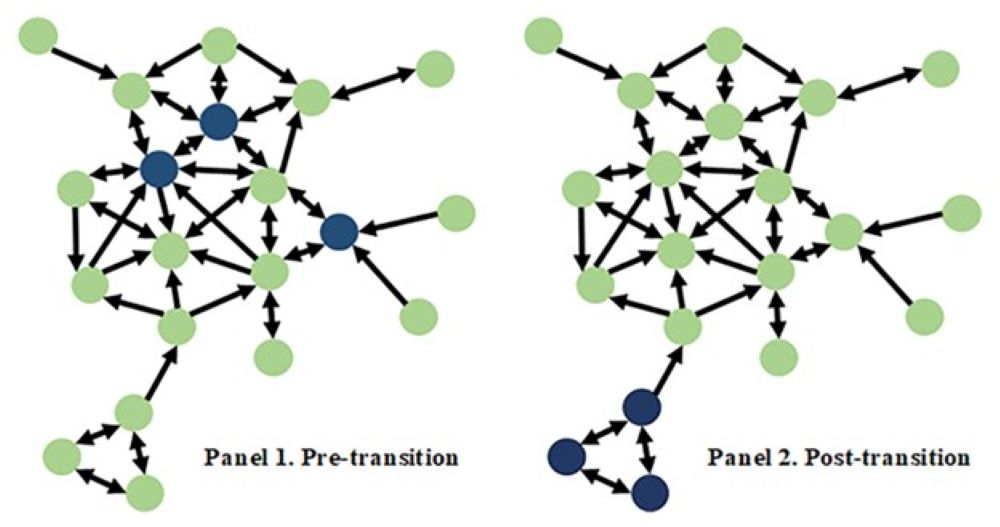

From this data, McMillan generated social networks like those seen in Figure 1. In this hypothetical scenario representative of McMillan’s hypothesis, each student is represented by a node: green for prosocial students who engaged in no delinquent act, and dark blue for those with delinquent behavior. Students are connected to one another by “edges” — shown as double-ended arrows — that represent their friendships.

McMillan inputted the initial networks into a statistical model which uses formulas to predict who is exhibiting delinquent behavior before and after school transitions, as well as which relationships they’re maintaining.

The model found that delinquent youth often form isolated groups that move to the edges of social networks after a transition. These students became less “popular” as measured by the changes in the number of friend nominations a participant received from other students. This shift aligns with McMillan’s original prediction seen in the dark blue offshoot in Panel 2 of Figure 1.

“What seems to be happening is that after this transition occurs, the kids who are delinquent tend to be kind of pushed to the edges of their networks,” explains McMillan. “Which is good news for the kids who aren’t delinquent…[they’re] less likely to come into contact with delinquent peers who could provide negative influences.”

McMillan explains that delinquency tends to increase with age and usually peaks at 10th grade. But in both studies, this increase was smaller in districts that had a school transition than in non-transition districts.

In McMillan’s study of 6th grade to 7th grade transitions in the Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, student populations that underwent a school transition during those years saw less of an increase in average delinquent behavior than those who remained at the same school. They saw a 27% increase in delinquent behavior compared to a 36% increase in non-transition schools. McMillan concludes that this pattern is because of the tendency for delinquent students to become isolated after school transitions

Even as these changes lessen the overall increase in average delinquency that typically occurs as students get older, those prone to delinquent behavior may not necessarily become less delinquent.

“School transitions are likely to increase the risk that delinquent youth will continue or even intensify their involvement in these risky behaviors. This is because transitions push delinquent students into more precarious friendship groups that are associated with more criminal involvement, lower school performance, and worse mental health,” McMillan explains.

Not all students experience transitionary periods in the same way. McMillan found this to be true for delinquent and prosocial students, but she is curious about what other characteristics impact how we evolve through school transitions.

“So what we’re hoping to do next is unpack [which students struggle with transitions] by looking at various types of inequality that students face like differences by socioeconomic status, by race, by gender… How do these differences impact adolescents’ experiences with normative school transitions?” McMillan says.

Although McMillan plans to expand her research about school transitions, there is still much to be learned from these pilot studies. As McMillan’s social networks show, this is a time in which adults should be mindful of the changes students may find in their social lives and behaviors.

“These transitions have to happen in most school districts, but understanding how we can make sure that we are giving kids the resources that they need [will help] to ensure that they’ll be able to succeed in their higher level schools,” says McMillan.

Story from the Science Media Lab.

Last Updated on November 29, 2023